Fragments of You and Me

PUBLIC ART

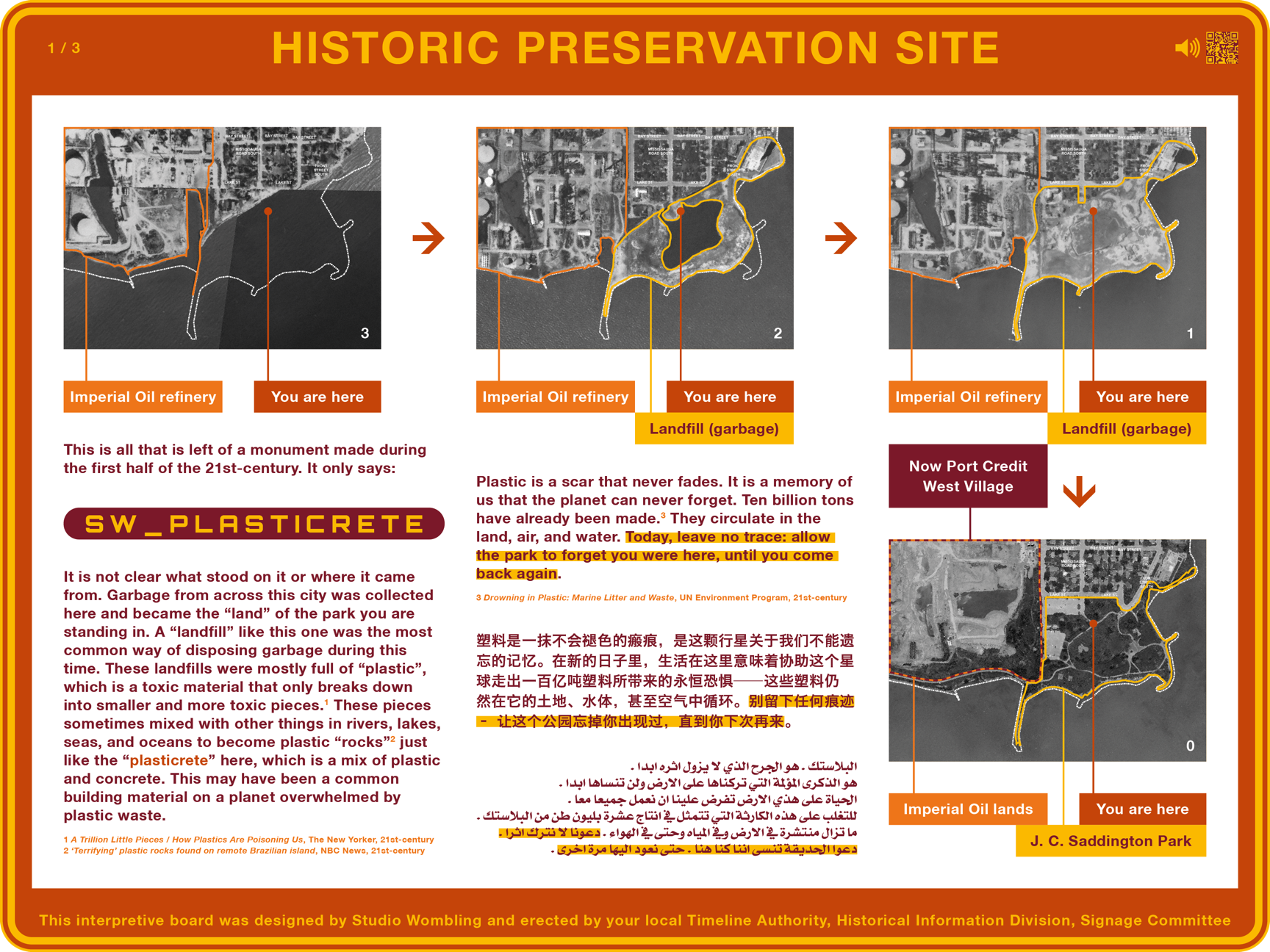

Two empty plinths, cast from concrete mixed with collected plastic litter, and three plaques in Mississauga’s J. C. Saddington Park address the complexities of our collective relationship with plastic. The plinths function as “plausible objects”: things which the plaques could plausibly seem to refer to, although what the plaques actually refer to is the invisible network of production, consumption, and disposal of plastic. The plaques follow public information design standards for parks and historic sites in Canada, but are written as though by a municipal authority from an alternate timeline where plastic is no longer the problem it once was.

1. WHAT IS THIS?

Some ten billion tons — or ten trillion kilograms (10,000,000,000,000 kg) — of plastic have been manufactured so far, at a rate that increases every year. In this decade, we have produced nearly a billion tons of plastic every two years. It is difficult to even imagine what that number means. More difficult still to consider the fact that of those ten billion tons, less than 10% has ever been recycled. The remainder is simply — out there, circulating in even the most seemingly pristine environments you will ever encounter on this planet.We imagine that in such a world — where even the ground beneath your feet consists of buried plastic — plastic waste will begin to be used by its citizens as a building material, like in the pedestal you see before you. This plaque assumes you are a citizen from a future beyond even that time, where the problem of plastic has been dealt with, and where its horrors remain only a historical memory.

PLAQUE REFERENCES

- Kolbert, Elizabeth. A Trillion Little Pieces / How Plastics Are Poisoning Us. The New Yorker. 26 June, 2023.

- ‘Terrifying’ plastic rocks found on remote Brazilian island. NBC News. 16 March, 2023.

- Drowning in Plastics — Marine Litter and Plastic Waste. United Nations Environment Programme. 21 October, 2021.

2. WHAT IS TO BE DONE?

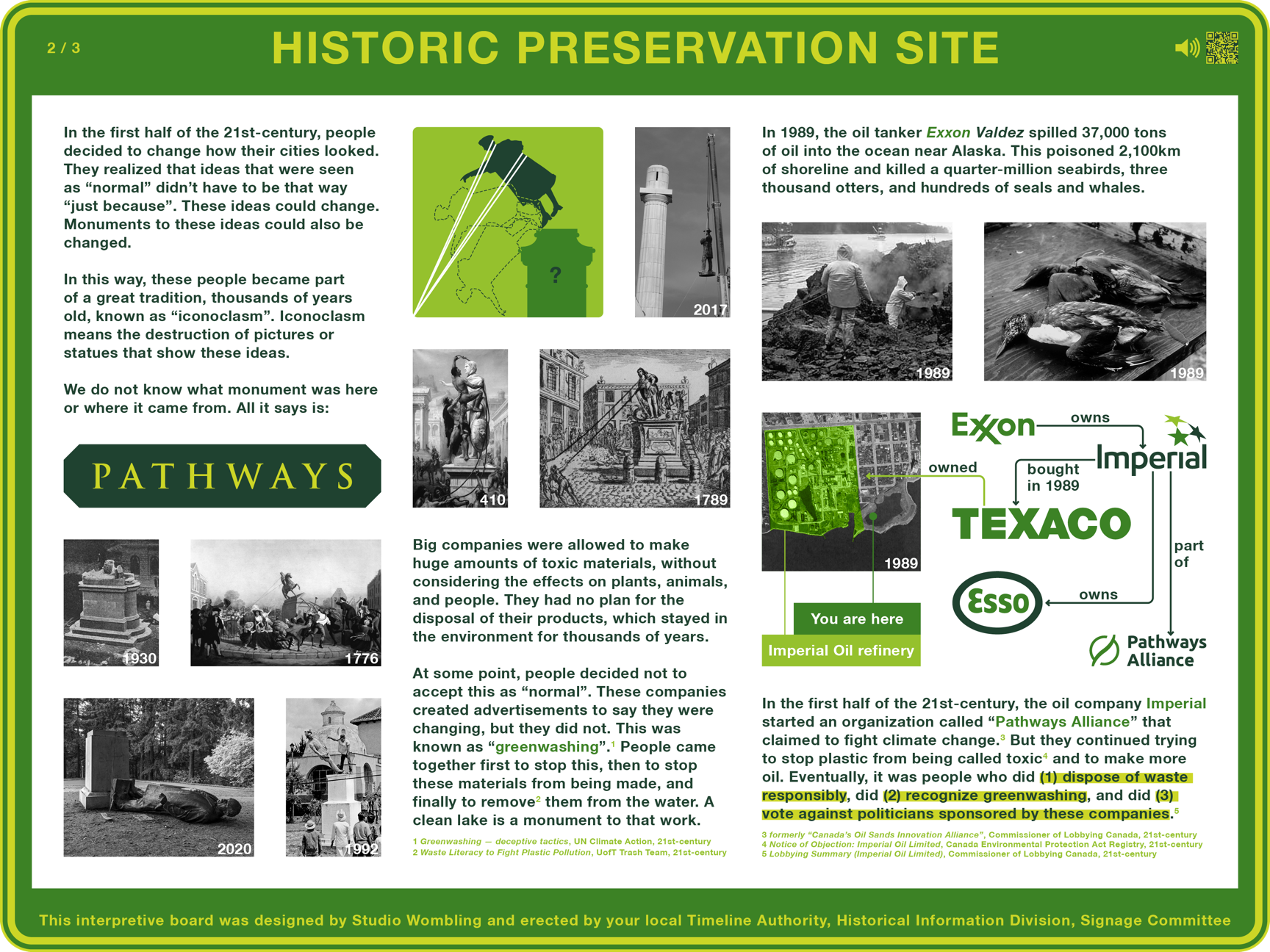

You know, of course, to dispose of your own plastic waste carefully. But what has led to plastic’s widespread availability, and why is its disposal so difficult? Plastic is a petrochemical, and its production and disposal heavily influenced by corporate interests in government, especially in a country as closely tied to the petrochemical industry as the one we live in.Not only has the vast production of plastic been made to seem normal — Coca-Cola has increased its production of plastic by millions of kilograms every year — but the disposal or recycling of this plastic has been made to seem our individual task. Never mind that it is hardly possible for an individual to collect the kind of machinery and chemicals required to construct a single-purpose bottle-recycling plant in their backyard to recycle a bottle of Coca-Cola, or for even a municipality to build a plant capable of handling all of the thousands of varied products we all use. Not only have corporations denied responsibility for the afterlife of their products once they have accepted your money, they have also lobbied government to prevent them from being given any such responsibility. Instead, they have poured funding into “greenwashing” — expensive advertising claiming large-scale environmental victories on the basis of small-scale unfulfilled promises.

We must hold our political representatives to account for their close relationships with corporations that do not have our, our environment, or this country’s interests in mind. Imperial Oil, for example, which has lobbied government to prevent plastic being labeled as “toxic”, is owned by the American company Exxon, whose largest shareholders are “asset-management” corporations, and which is the successor to the 19th-century illegal monopoly Standard Oil. No corporate actions by it or its subsidiaries since then have suggested a turn away from the same kind of business.

Things need not remain the same. A recent law has effectively banned “greenwashing”, and oil companies have begun to take down advertisements and websites claiming their so-called environmental successes.* The next steps would be to increase corporate responsibility for recycling their own products, and to begin reducing the production of new plastics altogether. It starts by seeing the problem of plastic for what it truly is — your problem — a problem of selecting the correct waste bin, but also of selecting the correct box on an election ballot.

*Austen, Ian. Facing New ‘Greenwashing’ Law, an Oil Industry Website Goes Dark. The New York Times. 6 July, 2024.

PLAQUE REFERENCES

- Greenwashing — the deceptive tactics behind environmental claims. United Nations Climate Action. 2023.

- Waste Literacy to Fight Plastic Pollution / Pollution Prevention Projects. UofT Trash Team. 2023.

- “Pathways Alliance Inc.”, Registration — In-house Organization. Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying of Canada. 3 June, 2024.

- Notice of objection: Imperial Oil Limited. Canadian Environmental Protection Act Registry. 9 December, 2020.

- “Imperial Oil Limited”, 12-Month Lobbying Summary — In-house Corporation. Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying of Canada. 30 June, 2024.

3. IS IT COMPLICATED?

In a word, yes. The problem of plastic is incredibly complicated. This is partly due to the fact that the production of plastic is itself so long and complicated. Set aside the contents of your bottle of water for now; consider the bottle itself. The production of that plastic required, at its likely origin in this country, the complete destruction of wetland habitats and boreal forests along the Athabasca River in Northern Alberta. The extraction process there uses the fresh river water, and has left behind more than a trillion litres of “tailings”, which are ponds of the deadly chemical byproduct. There is enough to cover the entire lake you see before you, from Mississauga to Niagara, and from Hamilton to Kingston, in an oily crud half-a-foot deep. In Alberta, these ponds have also been leaking into the groundwater supplying communities in the region. Of course, this also means that the freshwater of the Athabasca River is no longer usable, a fact that underscores the absurdity of it being used to merely bottle freshwater collected elsewhere.Once processed, the raw material is transported mainly by pipelines — crossing and threathening communities, forests, rivers, lakes and habitats — from Northern Alberta all the way to Sarnia, Ontario, whose refineries make it home to 10% of all industrial air pollution in the entire province. Refineries in Sarnia produce so much air pollution that some have been granted exemptions from legal pollution limits by the province. The plastic raw material produced by these refineries is then transported by rail or road to a bottling plant, such as Nestlé’s plant in Aberfoyle, about 45 minutes’ drive from here.

The water itself is extracted in the town of Erin, about 30 minutes’ drive west of Brampton. Here, Nestlé has an agreement to pay the province $503.71 per million litres of water, which works out to nearly 2,000 litres of water per dollar.* Unsurprisingly, local communities have no access to clean drinking water, and similar communities have not had access to clean drinking water for decades — in a country home to 60% of the world’s lakes and 20% of the world’s freshwater. Residents must drive to nearby Caledonia, to purchase their own clean water, now bottled by Nestlé and on sale for about 2 litres per dollar — a thousand times more than Nestlé paid for it.

The bottled water is also transported from the bottling plant to your local supermarket, where you purchase it, and having consumed it, wish to dispose of the plastic responsibly. Unfortunately, Nestlé has refused any responsibility for it’s product past this point, and the province or municipality must develop the collection protocols, transportation network, and recycling technologies necessary. The kind of plastic used in the most common kinds of disposable water bottle is polyethylene terephthalate or PET; you’ll have noticed an expiration date printed on these bottles; that expiration date is not of the water inside, but the date by when enough of the slowly decaying plastic container has leached into it that it is no longer recommended to drink it. These must not be reused, and can also only be recycled once or twice before they fall apart entirely into microplastics (as you can also tell by how flimsy the material is).

You have been persudaded by packaging — both literal and metaphorical — that bottled water is a product safely, easily, and cheaply† contained within its transparent plastic shell. However, a bottle of water is also a way of looking at the world — as a simple and uncomplicated place, without the relationships we have with each other and our environment. Packaging permits a bottle of water to masquerade as a singular product when it is in fact a waypoint along the long pipeline of extraction, a not-so-secret trans-continental violence against each other and the environment during which as little compensation as possible can be provided. Yes, you can and should throw your empty bottle in the blue bin, but in a complicated world, complicated problems require dealing with all of their complications.

*Shimo, Alexandra. While Nestlé extracts millions of litres from their land, residents have no drinking water. The Guardian. 4 October, 2018.

†Patel, Raj, and Jason W. Moore. A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things: A Guide to Capitalism, Nature, and the Future of the Planet. London: Verso. 2018.

PLAQUE REFERENCES

- Barlow, Maude. Boiling Point: Government Neglect, Corporate Abuse, and Canada’s Water Crisis. Toronto: ECW Press. 2016.

- Carrington, Damian. Microplastics revealed in the placentas of unborn babies. The Guardian. 22 December, 2020.

Project by Ameen Ahmed and Lara Hassani

/ 2024-2025 / J. C. Saddington Park, City of Mississauga

/ tagged art

︎

OLDER︎︎︎